Between my An American Girl Anthology book tour and my children’s school year rapidly coming to an end, I am running on fumes and far too much iced coffee. Our household is also in that strange twilight state of lazy almost-summer late night dinners and also never having enough kid-approved stuff in the pantry for lunch-making. Around this time every year, I devolve to eating peaches and whole tomatoes over the sink with a hefty balance of packaged crackers, leaving a trail of dusty crumbs from the kitchen to my office. Sometimes, when I’m feeling peaky, I reach for the peanut butter sandwich crackers. You know the kind. We always seem to have a box or two in the cupboard. This hectic time of year they become the stand-in for lunchtime mains, a perfectly mid hefty snack, and the lamest poolside nibble I can routinely dig up from the bottom of my oversized tote. And in this spirit of time-crunchiness, I turn to one of my previous writings on peanut butter crackers, written as part of a food writers’ conference back in 2020. Full disclosure, this event was co-sponsored by Lance and I was given access to the Lance archives. There were plans to publish this somewhere, do more work with the archives, but just two months later, the pandemic hit. Wild times! Enjoy!

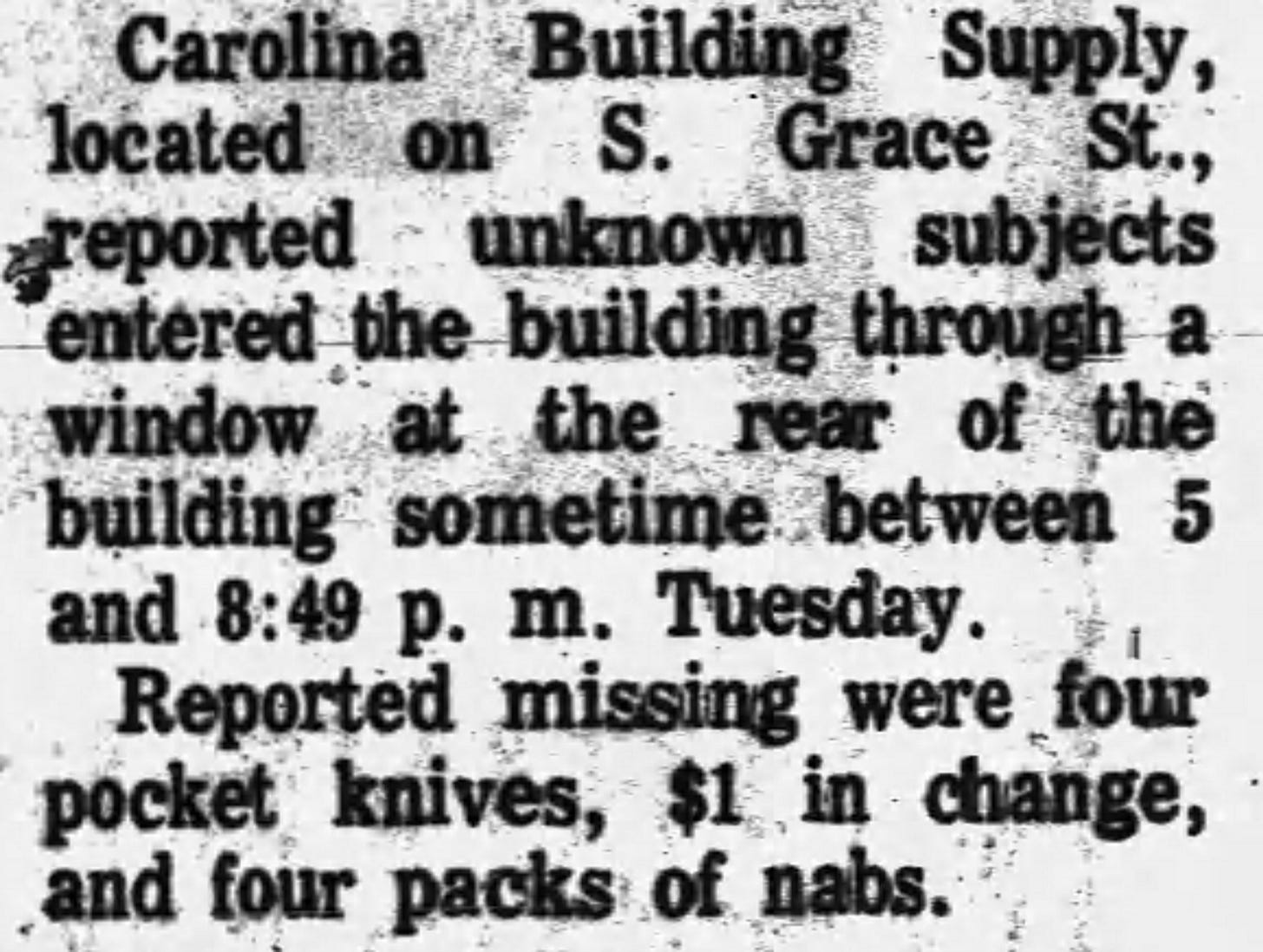

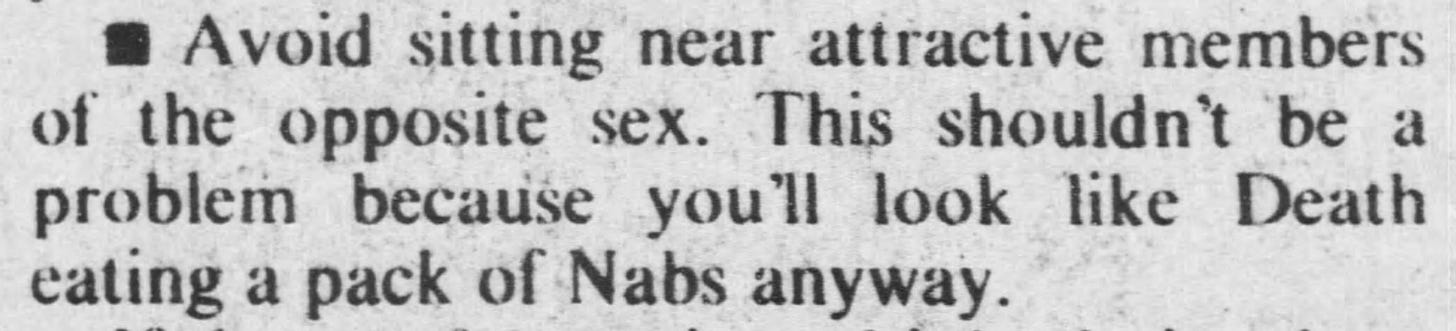

Nabs, as they’re called in this part of the South, were made for hurried people. Even their name invokes a sense of urgency. Shortened generations ago from the longer Nabisco, one of the earliest brands to market peanut butter sandwich crackers, Nabs became the catch-all term many southerners apply to any pack of plastic-wrapped cracker sandwiches. Lance now reigns supreme for snacks in the south and the peanut butter cracker remains one of their mainstays, though the company in their 100 year history has never publicly called them Nabs.

The popular history of Nabs is hurried, too, and often overlooks the collaboration that brought the snack to life. Dozens of articles detail the enterprising origins of the Lance Packing Company founded in Charlotte, NC in 1913, when Philip Lance and his son-in-law Salem Van Every were stuck with 500 pounds of raw peanuts from an unsuccessful food brokering deal. Most articles skip to the part where the two men eventually moved their bustling peanut butter packing business into a new downtown warehouse, which later became Lance, Inc.

Here's another version: Lance and Van Every came home from work with an obscene amount of seemingly useless raw peanuts. Their wives, Nancy Henning Lance and her daughter Mary Arnold Van Every, suggested they roast the nuts in their home kitchen and turn them into peanut butter to sell to hungry workers in the city. Instead of taking all the household spoons for doling out samples, the wives likely suggested sandwiching the peanut butter between two crackers, creating the first Lance brand peanut butter sandwich crackers (or Nabs, if you will). "We credit the women," says great-great granddaughter, Quincy Foil White, who believes that Nancy and Mary likely wanted the two men and their growing business out of the house and out of their kitchens.

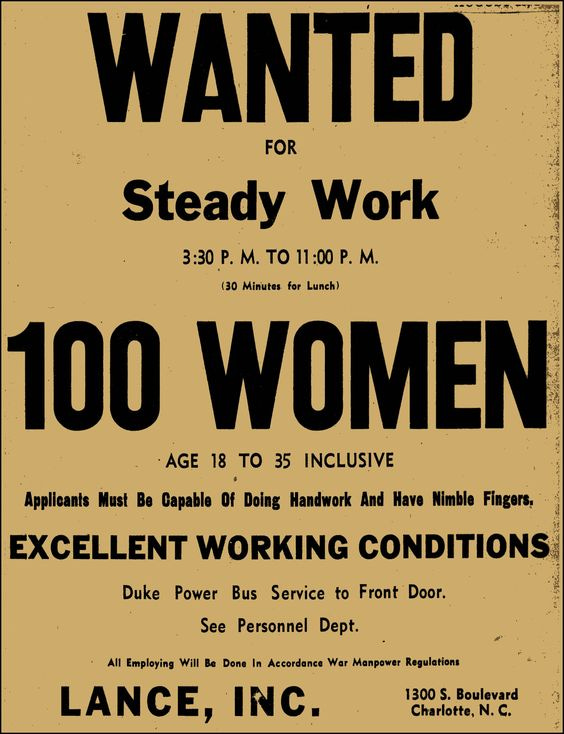

While the Lance family women helped launch the snack company, women across the United States were reshaping American foodways by entering the workforce. With additional income and less time for home cooking, many working-class women, still burdened with the task of meal planning, turned to the broadening array of packaged foods to help feed their families. From hurried workers in the 1920s to hungry teens on the move in the early aughts, Lance capitalized on American consumers' need for affordable convenience foods with speed-focused slogans including "Don't Go 'Round Hungry," "A Square Meal in a Minute," "Lance on the Go," and, my favorite, "I got Lance in My Pants."

According to Philip L. Van Every, grandson of the original founder and the third president of Lance, Inc., people were one of the company's greatest assets. From the women who kept the factory running during the labor shortages of World War II to the mill workers of Charlotte and across the southern United States who grabbed a pack of Nabs from a factory dope cart during one of their long shifts, the Lance company and its crackers kept generations of hurried southerners employed and fed.

For the descendants of the Lance family, no matter how hurried they might be, the term Nabs doesn't give the crackers their due. Great great-granddaughter Quincy avoids the term. "In our family we never called them Nabs. Our products had such great names. I prefer to use those." And for the price of a single extra syllable—Toastchee, NipChee, Toasty—those names are relatively efficient. Though a Lance cracker by any other name, would still be a Nab to most southerners.

I just bought a box of pb crackers & they really do hit the spot!

i've never heard that word what the heck!

i'd like to do a blind taste test between lance, keebler and ritz.

all flavors!