"A rotten recipe stealing b*tch"

A brief legal and cultural history of recipes, hashtags, and women's labor

This week, I’m on spring break (or rather my children are), so I’ve brought in a substitute food history professor. Sike! It’s just me sporting my doctoral hood and gown like when Wishbone would start the episode as a Jack Russell Terrier explaining some great work of literature and then the scene would cut to the main character of the story, but wait, it was also Wishbone! You get it!

For this substitute guest lecture, I’ve pulled up an old conference presentation about the legal and cultural contexts of recipes and hashtags, where those two meet, and the often-uncompensated women's labor behind them both. Queue the projector!

It began with a recipe, but it wasn’t just a recipe. It’s never just a recipe.

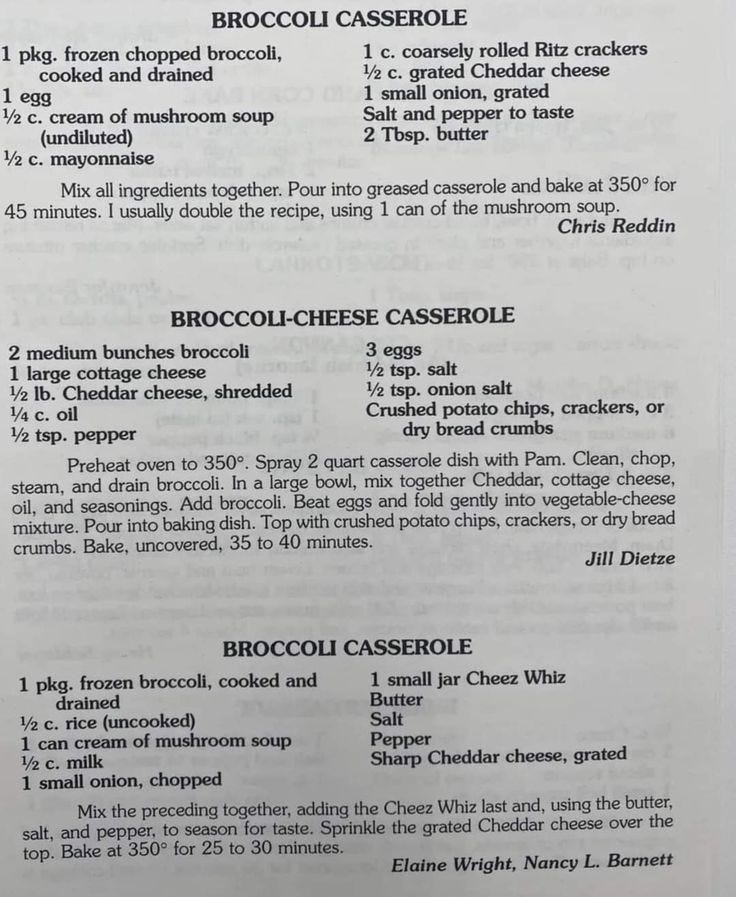

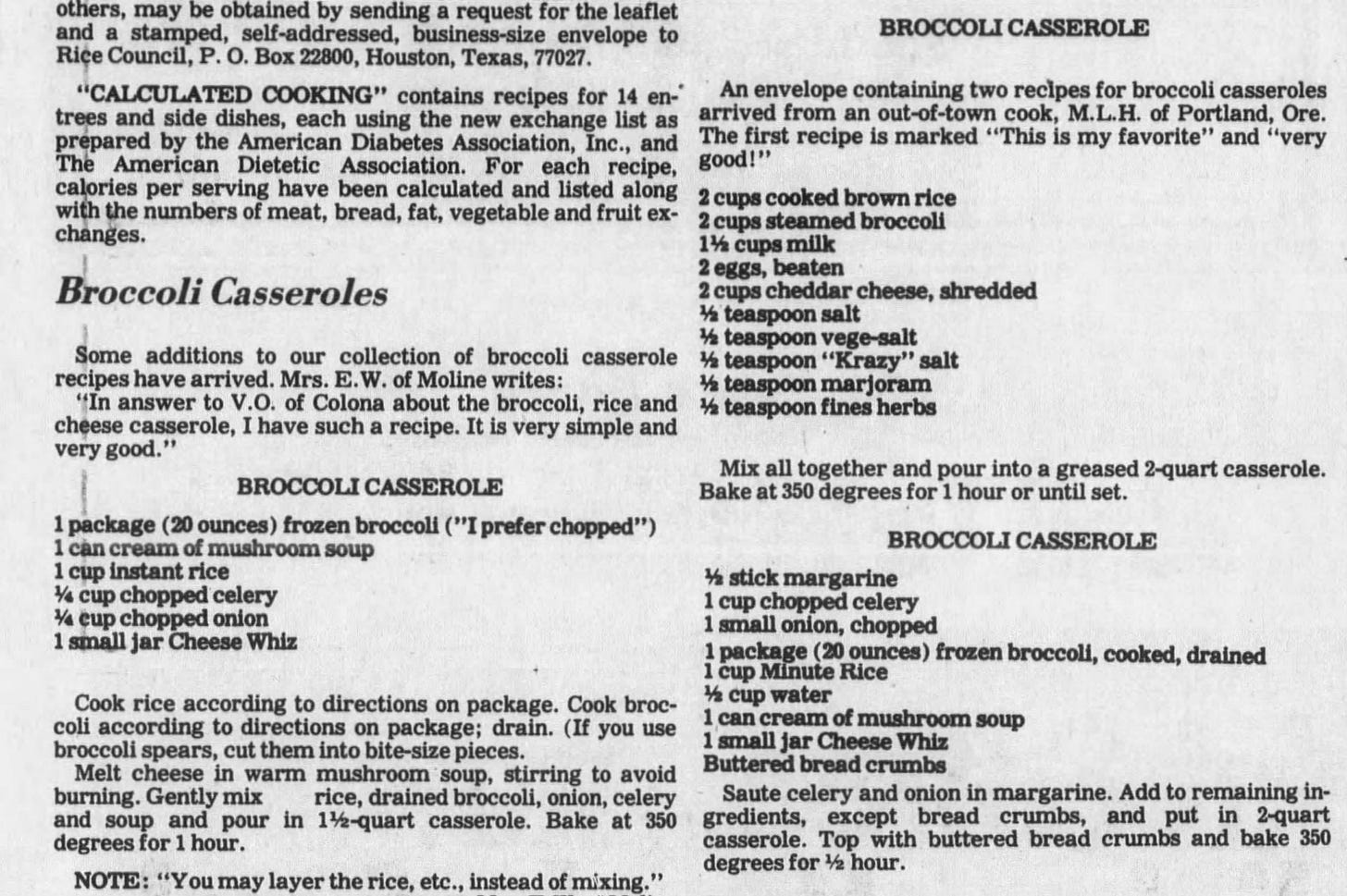

This video was originally posted on TikTok in December 2020 by the artist Lubalin who often posts these types of short parody videos which he calls "Turning Random Internet Drama into Songs." This particular video sourced the so-called drama from a Facebook interaction between several women over recipe attribution. If you didn’t watch the video yet, now’s the time to scroll back up and do so (sorry not sorry for the inevitable earworm you’ll get).

The “she stole my broccoli casserole recipe - internet drama part 2” video garnered over 40 million views, led to numerous other drama song videos that similarly went viral, and promotional spots with folks like Jimmy Fallon on national TV. Of course, we don't know if Lubalin is aware of the long history of the lack of accreditation and respect for women's recipes and food labor, but public response to his video, more than double the likes and views than all but one of his other "internet drama" TikToks, shows that his choice of topic resonates with viewers who are entertained by what is portrayed as a petty perhaps even silly argument or grudge.

I use this video, not to call out Lubalin and his absolutely delightful singing voice, but to demonstrate how we as society on the whole think about the authority and ownership of women's food labor and recipe production.

In a world mired with obscure ownership rules and often tedious legal codes, there are two areas that remain relatively untouched: recipes and hashtags. These are two areas that couldn't seem more different, but are linked by the invisible labor and the overwhelmingly female-identifying base that create them. Passed down through generations or made viral in a matter of moments, these two elements of intellectual property have very little legal protection under US copyright and trademark laws. The lack of regulation is due, in part, to the common and public usage of both, but capitalism has turned recipes as well as hashtags into commodifiable parts of an content economy that prioritizes ownership and intellectual property production.

While recipe and hashtag accreditation has always existed, both rely on an unofficial code of ethics and citational politics that encourage collaboration and development (two hallmarks of feminist and women-centric communities). Despite this long history, recipes and hashtags alike are constantly appropriated without proper credit; the digital world has only further disproportionately disenfranchised women's intellectual property and labor.

In the US, intellectual property can be legally handled via copyright, trademark, and patent. And note, the patent process isn't really viable here, because it requires novelty. And recipes are rarely novel and those that are require the process by which they were made be patented rather than the resulting dish itself (for example, how a popsicle was frozen, rather than the popsicle recipe itself). So food companies and food science organizations might use this process, but it doesn't really apply to restaurants, chefs, home cooks, bloggers, etc. There's also the concept of trade secrets (like the recipe for Coca-Cola or the KFC spices), but those aren't meant to be shared, they are literally SECRETS and not really part of this side of the conversation.

The US has issued some more specific language regarding recipes:

"A recipe is a statement of the ingredients and procedure required for making a dish of food. A mere listing of ingredients or contents, or a simple set of directions, is uncopyrightable. As a result, the Office cannot register recipes consisting of a set of ingredients and a process for preparing a dish. In contrast, a recipe that creatively explains or depicts how or why to perform a particular activity may be copyrightable. A registration for a recipe may cover the written description or explanation of a process that appears in the work, as well as any photographs or illustrations that are owned by the applicant. However, the registration will not cover the list of ingredients that appear in each recipe, the underlying process for making the dish, or the resulting dish itself. The registration will also not cover the activities described in the work that are procedures, processes, or methods of operation, which are not subject to copyright protection." 313.3, of the Compendium of the U.S. Copyright Office Practices

A hashtag is too short to be considered for copyright. For giggles, let's see how it works under trademark law. When determining whether a hashtag can be registered and protected under trademark laws, the US Patent and Trademark Office looks at several factors:

Types of services or goods being identified

Context

Use of the hashtag

Where the hash symbol is placed in the mark

As hashtags became increasingly more popular on social media, in 2013 the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) recognized hashtags as registrable trademarks “only if [the mark] functions as an identifier of the source of the applicant’s goods or services.” So very specific situations.

A few successful food-related hashtag trademarks include:

#HOWDOYOUKFC | KFC

#sayitwithpepsi | Pepsi

#ReachforPeach | E&J Brandy

These Trademarks are approved for use in storefronts, in-store displays, websites, print and digital advertising, and actual products and merchandise. Meaning physical, offline items. But at the end of the day, digital users can still use these hashtags in their original text-hyperlink format on social media platforms with little to no ramification. Only outside their hyperlink states can hashtags even carry the telling trademark symbol, and the practice of using big corporate or brand generated hashtags on non-relevant content is a popular method of tagging on platforms like TikTok.

What we can take away from these definitions are big overlapping concepts that make copyright and trademark unlikely options for both recipes and hashtags which include literal length (hashtags are too short), familiarity, public or common use, and, ultimately, the foundational concept of shareability. The creators made these pieces of intellectual property—these recipes and these hashtags—to be shared.

Instead of discussing the values of copyright or trademark (and whether those avenues would even be possible for small, independent content creators who typically lack the additional funds to pay the fees for these licenses, the time to navigate the legal code, or the bandwidth to watch for and pursue anyone liable for infringing on their trademark), let’s focus instead on the long, established history of citational practices.

Recipe attribution, or recipe citation, is a practice that has existed for generations in the recipe sharing world and is one that has been readily adopted by many digital users when sharing hyper-specific hashtags. These practices, according to scholars Martha Woodmansee and Peter Jaszi (authors of The Construction of Authorship) exist outside codified intellectual property laws, but still operate under sets of values involving collaboration, community-ownership, and exchange. But because they're different they are typically considered lesser, too.

In the recipe world, accreditation relies on a code of semi-formal ethics shared throughout the food industry from culinary professionals and home cooks to expert food writing publications and budding food bloggers. These ethics were built upon a system of understanding handed down by generations of women who used recipes and cooking knowledge as a form of communication, agency, and social acumen. We see examples of this in cookbooks (from large press publications to church and community cookbooks), private exchanges in letters and journals, and in recipe boxes where recipe cards literally have blank spots for the original recipe creator's name.

And when we talk about hashtags, I don't mean simple things like #food or #instafood or even something dish specific like #broccolicasserole, but arguably unique combinations of words that signify a specific event, concept, or creation. In the food world #pinefor started as a tag to share foods and kitchen spaces that people might "pine for" (started by @PineappleCollaborative), #bakersagainstracism (@bakersagainstracism) was launched by the handle by the same name as part of the global effort to raise funds for anti-racist groups in the wake of George Floyd's murder, and #foodartproject, founded by @thesouthasiankitchen, is a tag used by food photographers and stylists to share their work in monthly art challenges on Instagram.

In many cases, the origins of these hashtags are clear and their creators often add them to their profiles like a line in a resume. When users employ these hashtags on their own posts there is an expectation that the original creator's handle will be tagged or referenced in some way OR the tag is popular enough that most of their viewers understand its origins. If there's ever any confusion about the tag's origins, users can clarify in follow up comments, pointing others to the tag's beginnings. BUT the biggest difference here to print citations and accreditations is that hashtags are hyperlinks and create a literal digital map that can lead you back, with enough work, to their creators.

Let's turn to those creators of both recipes and hashtags. Throughout American history, food-related labor has been categorized under traditional gender roles. Women cooked domestically; men cooked professionally. So this leaves many of our contemporary food-content creators like bloggers and digital food content producers, who are overwhelmingly women, in a fairly precarious and unrecognized space.

On the digital side, women also face a similar path of gender discrimination. Women who work in digital spaces routinely suffer from the devaluation of their digital labor. While some of the earliest computer programmers and pioneers in the modern technological world were women, today's digital landscape favors male labor. The problem is not a lack of women working in digital spaces, but a narrative that celebrates men and overlooks women.

Feminist media scholars Brooke Erin Duffy and Becca Schwartz investigate this constructed divide through job recruitment ads for social media employment. Their research finds that the ideal digital worker possesses a set of features including "sociability and leisure; emotional management; and various types of flexibility." These expectations, they argue, inform and influence an "increasingly feminized nature of social media employment with its characteristic invisibility, lower pay, and marginal status within the technology field." Social media work carries an assumption of being "fun" and "hobby-like," in turn marginalizing the predominantly female workforce and their labor. This marginalization reinforces the invisibility of women's digital labor, a move that fits well within a larger capitalistic economy that devalues and delegitimizes other work traditionally associated with women...like recipe creation.

Now that we've refreshed our memories on the gendered landscape of both the food industry and the digital world, let's return to the specifics of recipes and hashtags. We know there are countless examples of recipes being shared without proper citation on blogs, social media, and in informal print, but let's look inside the "professional" side of the food industry, where we still find this gendered labor and accreditation dispute in full force.

Some restaurants add specific language in their contracts that explain their food labor as "work for hire," which according to the U.S. Copyright Office, means “an employer is considered the author even if an employee actually created the work.”

Even if chefs turn to print, there isn't a guarantee their recipes are protected, as scholars Tippen, Hakimi-Hood, and Milian discuss in their research on Maria Eliza Rundell's A New System of Domestic Cookery published in 1806. They found that Rundell's publisher John Murray tried to retain complete control of the publication rights for her recipes and later when the book was re-published numerous times in the US she received no additional royalties.

To help navigate the unclear nature of recipe IP, especially in today's digital landscape, organizations like the now defunct Food Blog Alliance, provided guidelines for bloggers on how to handle other peoples' recipes. The subgroup, The Austin Food Blogger Alliance provided the following as part of their code of ethics:

We will follow the rules of good journalism

We will not plagiarize. We will respect copyright and ownership rights to photos. We will attribute recipes and note if they are adaptations from a published original. We will research. We will attribute quotes and offer link backs to original sources whenever possible. We will do our best to make sure that the information we are posting is accurate. We will fact check. In other words, we will strive to practice good journalism even if we don’t consider ourselves journalists.

In addition to these published guidelines, chef evaluations, and journalistic codes of ethics, law and media scholars have pondered numerous methods of how best to approach this complex and ever-evolving topic. But none of them have been put into place nor do they help challenge our understandings of authority and ownership.

The original moral laws and collaborative ethics that covered recipes, and now hashtags, while admirable, are failing to keep up in an increasingly consumer-driven capitalist world that prioritizes proven originality and ownership over open-access. The "spirit of the craft," as Chef Wylie Dufresne calls it, that encourages food-creators to learn from and share with each other does not extend the same equitable considerations when it comes to the gender disparity in food labor and compensation.

As Lubalin sings, when it comes to recipes and hashtags, you do really have to be careful who your friends are.

Just the words “broccoli casserole” and I knew where this was going. Thank you!