Over the past few months, I’ve talked to lots of folks about Election Cake and election related foods. I spoke with Jenny Comita about the power of political cakes for T: The New York Times Style Magazine. I chatted with Todd Price at USA Today about Vice President Kamala Harris’ love of cooking and the historical precedents of the women in federal offices and positions of power before her. And just last week, I unpacked Trump’s problematic eating habits within the larger cultural context of food and politics with Rachel Belle of the Your Last Meal podcast. I appreciate each and every opportunity because it’s a chance to highlight the power of food and demonstrate how everyday decisions that I, your grandma, and even the Vice President of the United States make about food have important political implications.

Election Cakes are often a favorite talking point because, well, I think the majority of folks still find cakes frivolous, surprising, and perhaps even unworthy of the gravitas of politics. And it just so happens that Election Cakes are historically associated with women who, until quite recently in the grand scheme of things, couldn’t vote let alone hold federal office. Although steadily increasing over the past century, women only made up 29% of the House of Representatives and 25% of the Senate of the 118th U.S. Congress. In June 2022, the white male dominated U.S. Supreme Court (in this case Barrett and Thomas both count as while males because they voted like one) overturned Roe V. Wade stripping women of fundamental rights to reproductive health care. And I’m sure I don’t need to remind you how the last female Democratic presidential candidate was treated during her campaign in 2016. Outside of the food community, Election Cakes remain a silly little historical sidebar because that’s how many people still perceive women in positions of political power.

Historically, Election Cakes were simply cakes that fed a lot of people during election times, which were large in-person gatherings during the colonial era. Only white, male property-owners twenty-one and older could vote. Elections drew voters from their various properties to a central location, usually a large town or colonial capital, so travelers would often extend their stays or add other stops along the way. While women couldn’t vote, they could bend the ear of the voting-eligible men they hosted on election day. And at the very least, serving slices of cake allowed them access to political conversations they might otherwise miss.

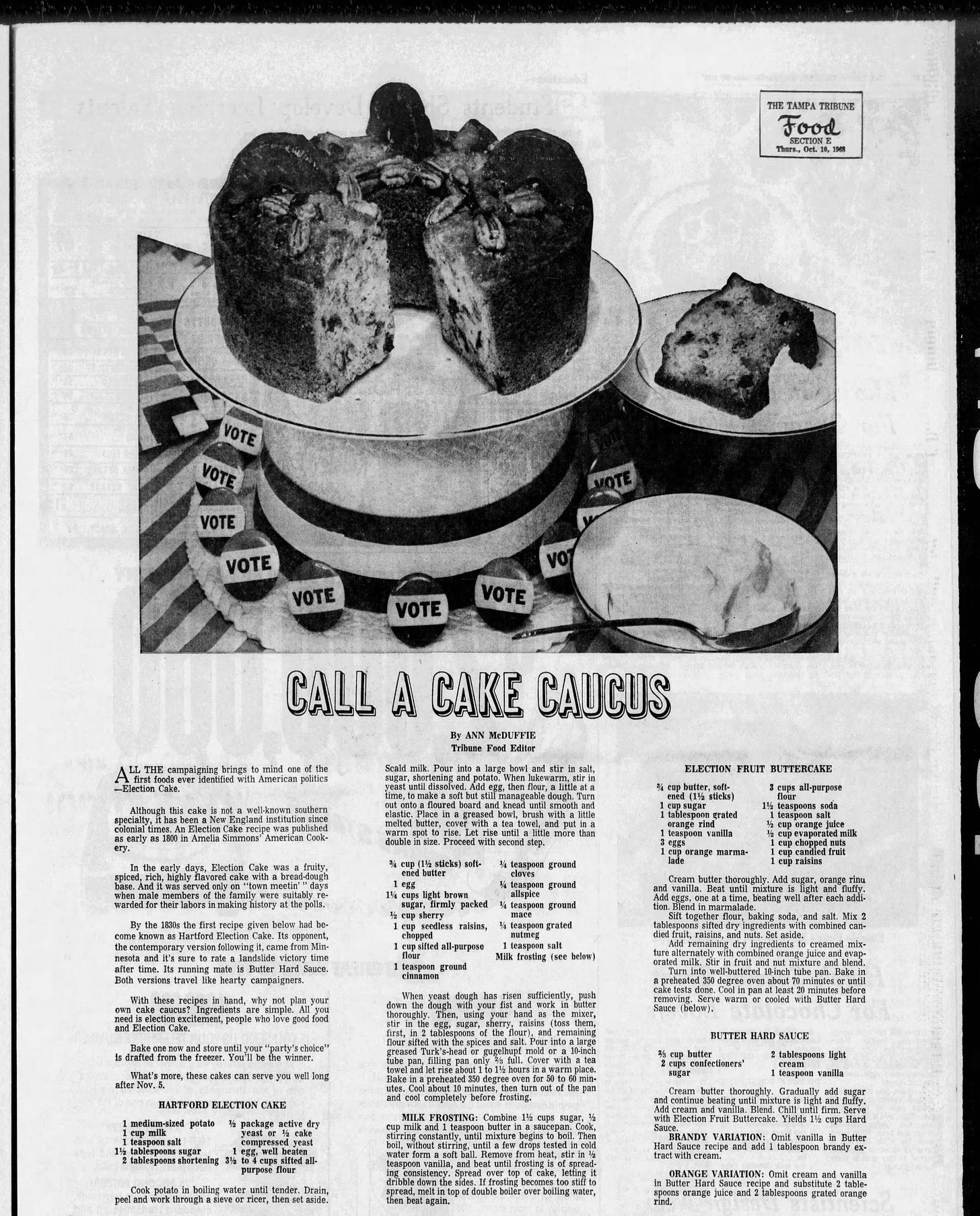

The cakes themselves were traditional English style “plumb” cakes, a dense, yeast-risen and heavily spiced cake studded with dried fruits, spiked with spirits, and often frosted with a white icing that hardened over time. These cakes could be made in great quantity and were effectively shelf stable; they were the perfect bake for feeding a crowd of hungry voters who could arrive at various times. At this time, these cakes weren’t called “Election Cakes,” a term that would become popular a couple of decades after the American Revolutionary War. While some early American cookbooks included recipes for Election Cakes, they were largely indistinguishable from other cakes that were baked for similar big occasions such as weddings, funerals, and family gatherings. In her book American Cookery, Amelia Simmons’ Election Cake called for 30 quarts of flour, 10 pounds of butter, 14 pounds of sugar, 12 pounds of raisins, and 3 dozen eggs. Scaled down, her Election Cake is quite similar to her recipe for “Plumb Cake” and “A Rich Cake.”

As America the country was born and quickly evolved, Election Cakes became associated specifically with Hartford, Connecticut, a community that spared no expense in hosting lavish patriotic parades and balls to celebrate the election process. One of the most well known versions of the Hartford Election Cake comes from Hartford Election Cake and Other Receipts by Ellen Wadsworth Johnson published in 1889. The book contains twelve different (slight) variations on the traditional cake submitted by various women from Hartford and the surrounding area.

Despite the heavy reliance on food and cooking as part of the national suffrage movement, Election Cake was already a relic of the past by the late 1800s. The most well known suffrage cookbook, The Woman suffrage cook book (published in 1890), contained one recipe for "Mother's Election Cake" and was so styled because, after a century or so, "election cakes" were out of fashion and baking technologies and trends had advanced significantly thanks to gas ovens and packaged baking powder. Other cakes, especially those dressed in traditional Suffrage colors, became important elements of the early 20th century women’s movement, but those cakes don’t fit this narrative of Election Cake history. A tidy story connecting generations of American women and a singular cake recipe quickly seems to, if I may use a baking metaphor, curdle and separate like an over whipped buttercream that still tastes fine, but looks a little messy.

I don’t like the way most folks talk about Election Cake and the women who baked it. Every decade or so around a big election season, the Women’s Pages in newspapers ran exclamatory features with recipes about Ye Old Election Cake and how wild it was that cake could hold such historical power. And it’s always the same old story—look at those old colonial women doing what they could—and always told in a very demeaning, patronizing way. Exceptions include baker and food writer Keia Mastrianni’s coverage of the Old World Levain bakery in Asheville who started a Make America Cake Again campaign back in 2016. The bakery shared an updated Election Cake recipe on their website and were, as Mastrianni reported at the time, motivated to honor history and “reinvigorate the lost levity of the democratic process.” I also appreciated reading Election Cake insights on the labor required for keeping yeast in early American homes from baker Amy Halloran (author of the substack newsletter Dear Bread) last night as I finished rage writing this post. It reminded me of the Election Cake surge during the pandemic in 2020 when people turned their newborn sourdough skills to yeasted cakes during the campaign season. That’s the same year I started to really notice the other cakes in bakeries across the nation and on Instagram tagged with #electioncake.

Because election cake isn’t just a particular recipe, it’s an exercise is everyday politics. It’s a statement of community organizing. It’s a message from when women didn’t have an official voice and from now when women and many other marginalized groups still need others to help ensure their basic human rights. So to those who ask about the history of election cake, I will tell them about the colonial women who spent weeks saving loaf sugar, drying small fruits, and rationing spirits to make yeasted fruit cakes topped with a hard white icing that fed all the hungry men who came to town to vote. And to those who ask about election cake in general, I’ll tell them that any cake can be an election cake. A colonial-era inspired fruit cake you make in your 21st century kitchen with a little packet of yeast that you probably wont like the taste of in the end. A chiffon cake frosted in the suffrage green and purple. A towering layer cake covered in shredded coconut in a nod to Harris’ coconut tree comment. A cake posted on the Sweet Feminist Instagram feed that haunts JD Vance’s dreams and makes him spew falsehoods so incorrect that someone as icky as Joe Rogan has to correct him. A cookie cake piped with messages with a quote from a candidate, the stakes, or even just the words “VOTE.” All the beautiful cakes made by professional bakers like Paola, Natasha, Rose, Becca, and Doris who use their frosting-covered platforms for good, but also all the home bakers who fill the Internet with their different versions of #electioncake each election cycle. Those are all election cakes, too.

Those election cake histories are important (I’m legally obligated to say that as a degree-conferred food scholar), but the Election Cakes being baked right now in our local bakeries and in home ovens matter more, especially this time. Largely because they represent all the progress American women have made and they remind us of all the work left to be done. This week’s Election Cakes are both a celebration of what we can do and a cautionary tale of all things we stand to lose.

Vote for women, vote for everyone, vote for Harris!

Pairs well with:

Still haven’t voted? Click this link to find out where to vote in your area on Election Day.