The rumor going around the grocery store candy aisle this Halloween is that gummy candies are in and chocolate is out. And while I totally understand Trick-or-Treaters’ predilection for trending cultural tastes over sweets that merely fit the holiday aesthetic, I fear for the cocoa-coated treats that might be going the way of the proverbial popcorn ball.

On its own, chocolate, of course, has nothing to do with Halloween and to quote a holiday expert Max Dennison: “everyone here knows that Halloween was invented by the candy companies.” Nevertheless, chocolate—especially the higher cacao-percentage varieties in both bar and cocoa powder form—have long been tied with The Dark, a concept steeped in metaphor and real-life social anxieties about the unknown. In physics, darkness merely refers to the absence of light. In literature, the concept takes on more allegorical meanings that often derive from real-life misunderstandings about the world that then frequently evolve to form foundational (and sometimes dangerous) binaries that we apply to everyday life. Light became right and dark became wrong and humanity kind of ran with it. In the worst situations this black-and-white thinking applied to people; in seemingly less bad situations it applied to things like socially preferable cuts of chicken (JK, that’s also about people). Chocolate, a naturally dark-hued food, got caught up in this way of thinking and swiftly became associated with darkness. Our cultural feelings about darkness evolved along the way, too, as something that was scary could also be fun and something that was maybe a little sinful or wicked could also be decadent.

For Halloween, a holiday celebrated at night and culturally marked as the time to welcome or ward off spirits with light (depending upon where you’re from), both literal and figurative darkness are important celebratory aspects. Thinking on campier, candy corporation-influenced versions of Halloween, that darkness is also represented by the caricatured creatures of the night—the vampires, witches, ghouls, and such—who canonically do their dark deeds when the sun doesn’t shine. Can you even imagine a devil making chocolate cake at 10 AM? It makes sense that chocolate, in its many shapes and forms, would eventually become a central flavor of Halloweentime festivities. Ever fearful that we are at a moment in which Nosferatu suddenly becomes addicted to the sinewy chew of Haribo, I’ve compiled a few of my favorite chocolate-as-darkness examples.

Midnight Cake (Betty Crocker, c. 1940s)

In the early 1940s, Betty Crocker rebranded Devil’s Food Cake for her Kitchen Clinic series that ran in newspapers across the nation. Barely chocolate, the cake called for just a half cup of cocoa powder (hardly close to Black Midnight!) and used baking soda to achieve that tell-tale Devil’s Food color and texture. Far more thematic is the suggestion to use Double Boiler icing, a known favorite of midcentury kitchen witches.

Count Chocula Chocolatey Breakfast Cereal (c. 1970s)

Chocolate isn’t relegated to post-prandial treats, but is also a featured ingredient in Count Chocula chocolatey cereal with marshmallow bits. I recognize that this isn’t an exclusively Halloweentime food, but surely sales soar around this season. The question is, why would a vampire like chocolate? Would it not make more sense for the character (even if he is named something ridiculous like Chocula) prefer something more akin to the life-sustaining blood he actually needs? For example, Count Mickula from Mickey's Monster Musical (2015) is always on the hunt for grape juice. Evidently grapes do not inspire the same type of spookiness needed to sell cereal.

Chocolate Marshmallow Witches

This now-bygone candy leaned on the classic early 20th century tradition of chocolate-coated marshmallows. Large candy companies including Brach’s sold these in special Halloween packaging for handing out to Trick-or-Treaters up until the 1960s. Why a witch and not a pumpkin or any other seasonal pick? My best guess is that witches are more fun to watch melt in your hot little kid hands or better for aggressively beheading with one’s teeth.

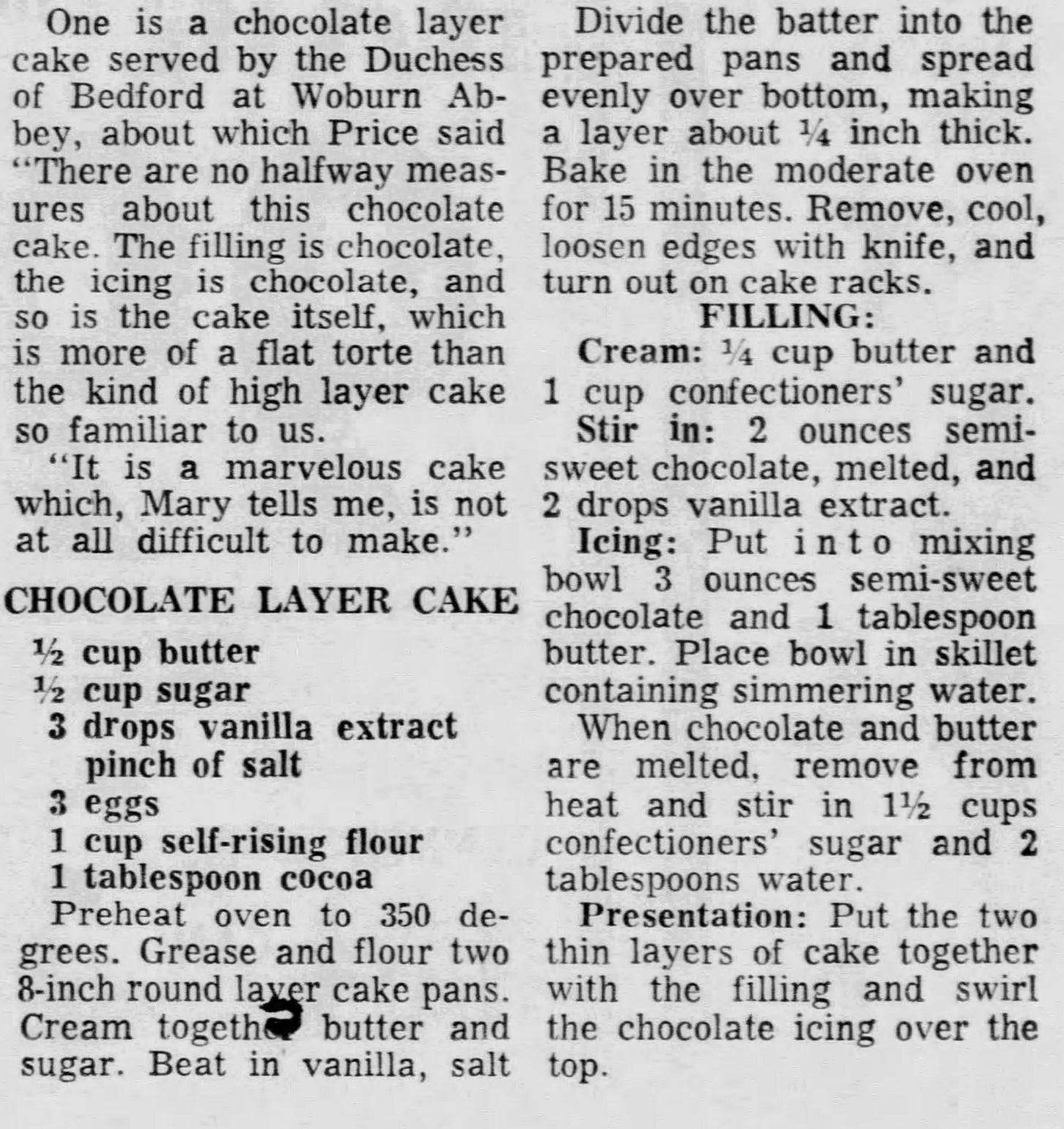

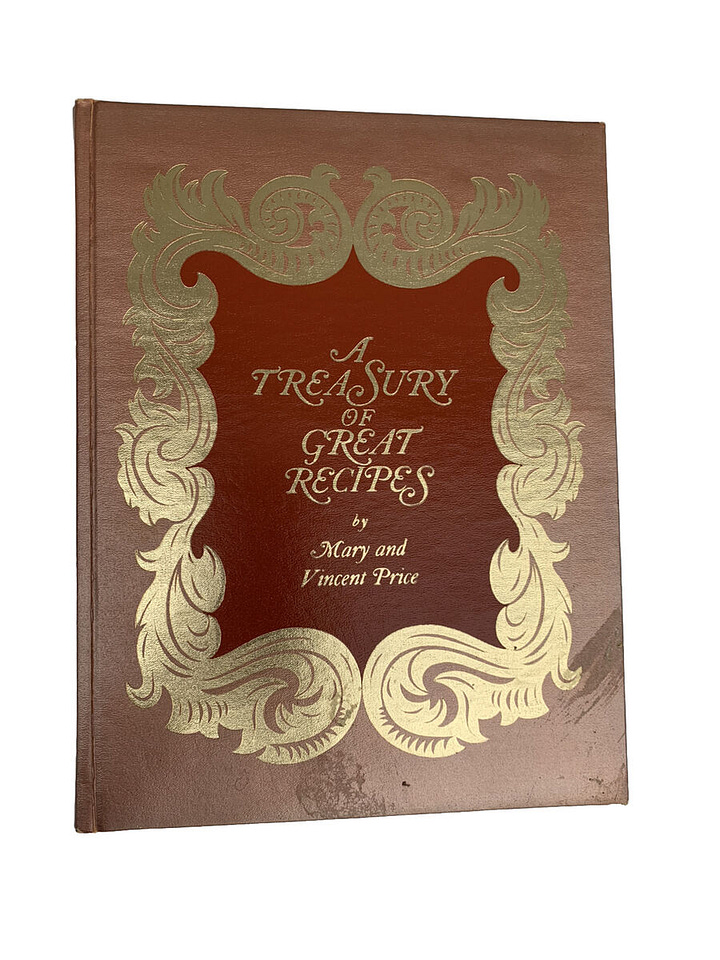

Vincent (and Mary) Price’s Dark Chocolate Cake

Grandfather of horror films and known for roles including the Invisible Man, Roderick Usher, villainous Professor Ratigan in The Great Mouse Detective, and The Inventor in Edward Scissorhands, Vincent Price was also famous for his love of food and cooking. Together with his wife Mary, the Prices published four cookbooks including A Treasury of Great Recipes: Famous Specialties of the World's Foremost Restaurants Adapted for the American Kitchen (1965). The arguably spooky-looking tome included a recipe for Price’s famous Chocolate Cake, also sometimes known as Dark Cake. In the 1970s, Price hosted a British cooking show called Cooking Price-Wise. While promoting the program on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, Price demonstrated how to poach a fish in a dishwasher, which is honestly far scarier than any chocolate baked good could ever be.

Low-Fat Devil’s Food Cakes/Cookies (aka Snackwells)

Not necessarily associated with Halloween, but still firmly in the all-chocolate-roads-lead-to-hell category, are SnackWell’s Cookie Cakes. Specifically the Devil’s Food variety that Nabisco could barely keep in stock due to such high demand in the early 1990s. One newspaper article from 1994 wrote: “SnackWell’s has evil ingredients: chocolate, marshmallow and devil’s food cake. But they’re fat free” (The Capital Times). Much like traditional Devil’s Food cake, the cookies used alkali to react with the cocoa powder “to bring out more chocolate flavor” (Glenn Collins, “Selling the Snackwell’s mystique,” The Miami Herald, 1994). The recipe called for far more sugar to help offset the lack of fat in the cakes. The SnackWell effect—a phenomenon in which consumers will eat more of a food if it’s labeled as less bad, better, or good for you, than they otherwise would, regardless of serving size—created a new cultural mythos around Devil’s Food and traumatized countless millennial children who witnessed their mothers’ diet culture-fueled descent into chocolate darkness.

Pairs well with:

Freshman year of undergrad, our first honors English assignment was to write our own obituaries. I chose death by chocolate; both a prophetic choice given my current career as well as a then-salient dig at the foodstuff that triggered relentless migraines during my late teens and early twenties. I tried in vain to find this assignment, so instead I’ll point you to one of my most favorite pieces I’ve ever written that still fits the theme: “Be Bad, Snack Well:” A History of Snackwells, Sin-Eating, and Cake Morality in American Culture. This piece was featured in Volume 2 of Cake Zine: Wicked Cake back in 2022.