Our FDA: she's imperfect, but she tries

a food history refresher on the importance of food regulation

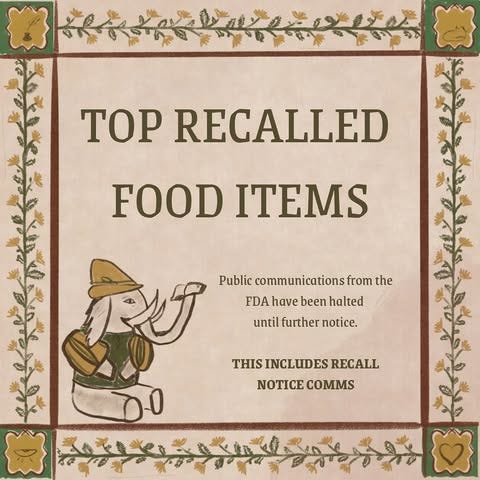

Just a few days after his inauguration, the Trump administration ordered an immediate pause on public communications from federal health agencies including the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) until February 1.

Many federal health agencies, such as the CDC, update their health tracking systems daily, so any delay can be problematic for consumers and health care professionals across the nation. The FDA updates their food and drug related reports with similar swiftness, especially when tracking life-threatening food recalls or updating the spread of the Avian Influenza and its impact on the national milk supply.

And, you might be thinking, 40-some years ago, we didn’t have websites or social media to provide immediate updates and we did just fine. Sure, we didn’t have those communication methods, but we also didn’t have the same magnitude of food system mobility or the amount of consumers or the rapidly breaking food system infrastructure that we do today. What we had then worked fine, but what we have in place now works even better. And even if there are technically more recalls and alerts, the consuming public is made aware of them even faster.

Effectively everyone currently living has benefited from the FDA. While it’s not a perfect regulatory agency, it’s also dealing with an equally imperfect food system. Could it use some upgrades, perhaps an injection of cash and additional staff, and maybe a little less pressure from Big Food Companies that care more about costs than consumers. Yes. Should we force them to cease communications with the consumer public (the main people at stake here) while we consider those upgrades? All together now: NO.

I’ll hold your hand while I tell you this next part: the policies that exist to keep our food systems healthy were created for capitalistic gain. Hold onto your strawberry Yoo-Hoo full of Red Dye No. 3, we’re going to rush through a couple hundred years of U.S. food history together:

The foundation for food policies to protect the public good was laid in 1787 when the Copyright and Patent Clause was proposed during the constitutional convention. However!…

No one really cared about food safety for a long time (this is clearly a generalization, but legally it’s roughly accurate).

The United States was, however, a largely agrarian economy and wanted protection for our bespoke seed varieties and fancy farming equipment. So a separate Agricultural Division of the Patent Office was created.

Through the Morrill Act of 1862, President Lincoln established the independent Department of Agriculture (but still wasn’t really worried about food safety, just focused on the success of our agrarian economy).

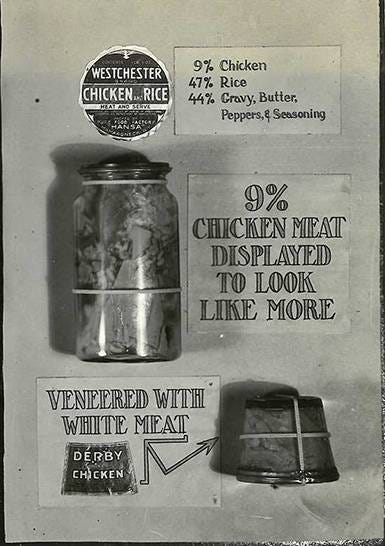

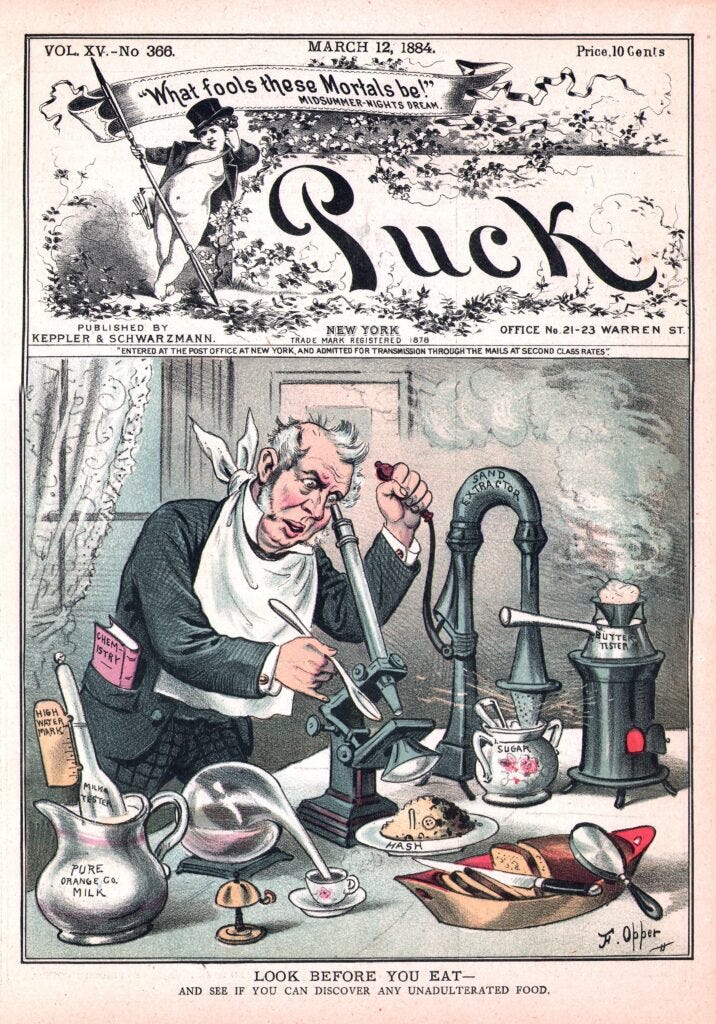

In the late 19th-century, thanks to muckrakers (remember that word from U.S. history class?!), including journalists like Upton Sinclair, the newly established US Department of Agriculture hired chemists to conduct research into food adulteration concerns in the American market. One of these chemists was Harvey Washington Wiley, who was eventually responsible for all sorts of wonderful food safety related innovations. Another important name at this time was Alice Lakey, a suffragist who is credited with mobilizing consumer support for Wiley’s work (she deserves a full post another time!).

In 1906, we finally (!!) get the Pure Food and Drug Act, which totally put American consumers’ health and safety as a top priority. Sike! In reality, it aimed to prevent “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of . . . deleterious foods, drugs, medicines, and liquors . . .” which sounds an awful lot like economic concerns to me…

Enforcing the regulations outlined in the new Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 became the responsibility of the USDA. After a reorganization in the late 1920s, a new regulatory body eventually known as the Food and Drug Administration was established and became one of the first wide reaching semblances of a food system safety net in the United States. That was less than 100 years ago.

Now here’s the tricky part. Late 19th-century food adulteration regulations and the establishment of the FDA largely happened because of a few loud spoken men who questioned industry norms. They weren’t even politicians (at first). They blew whistles on greedy capitalists who put profits over people and called out companies that filled their products with inedible ingredients that were widely known to cause bodily harm. Sound familiar? Sounds like RFK Jr. right?

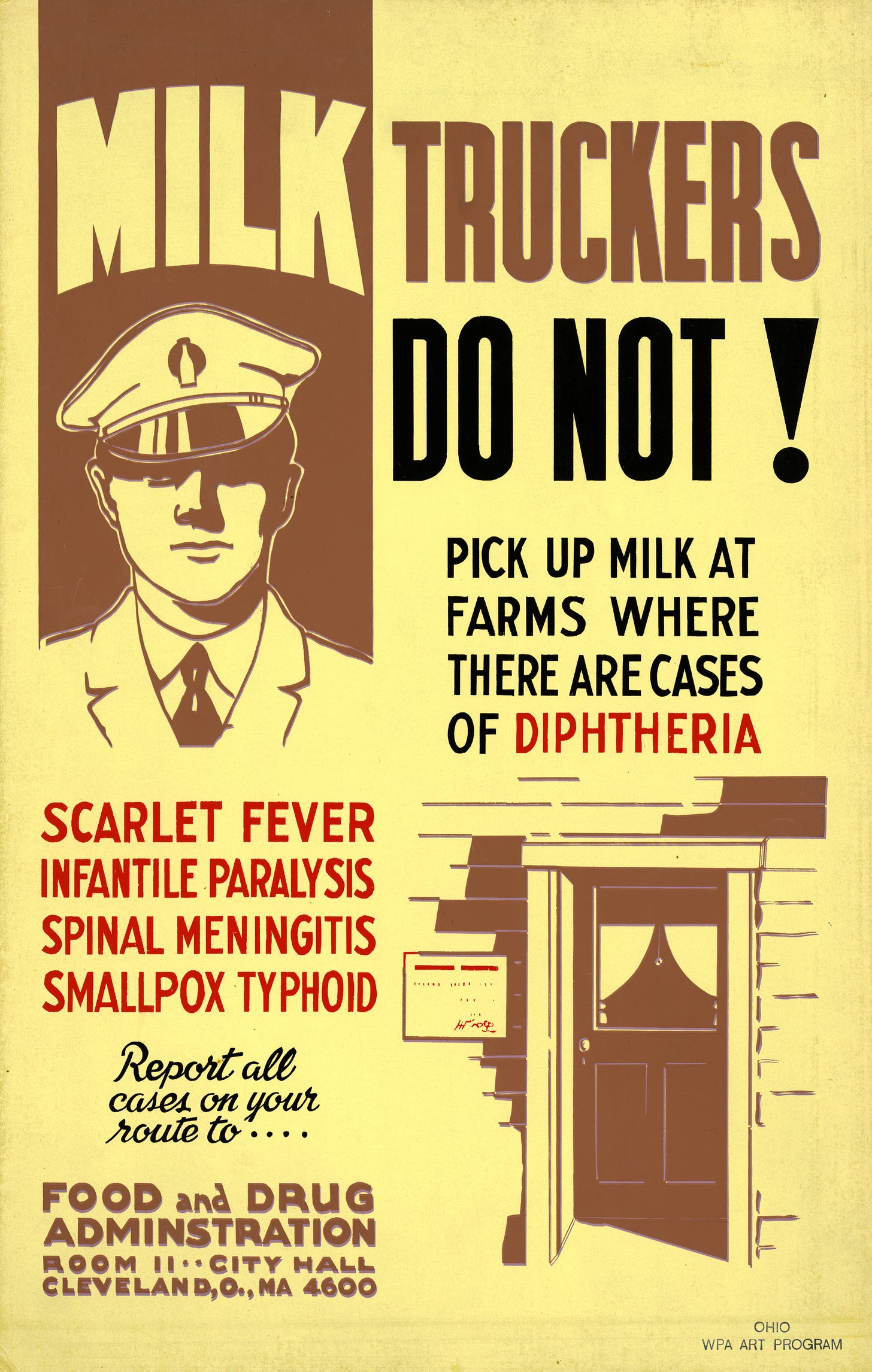

Now please hold my hand while I tell you this part: The rub here is that RFK Jr. isn’t necessarily wrong about the problems with our modern food system. Most of us who work in food would agree that Red Dye No. 3 is a harmful additive that should have long been banned in our country (as it already is in other nations). To be incredibly generous, I’ll give RFK Jr. this one, but that doesn’t excuse his consistent peddling in “half truths” as Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) described during his confirmation hearing earlier this week. We food industry folk might agree with him on the food dye and many other additives, but we also know that loosening raw milk regulations will be the cause of gastrointestinal peril as far as the eye can see.

This is why it is important to have a large team of scientists, food scholars, and a bevy of other of highly trained individuals working together to ensure our food system maintains a certain amount of regulation and that the decisions aren’t left to one individual who might have one good idea (though to be fair, it wasn’t exactly an original thought) along with a bunch of other really bad ones. A team like the Food and Drug Administration, for example. But if that team is told that it can’t communicate with the public, the very people it has been tasked to keep safe, we end up in a real recalled-due-to-botulism pickle.

Before our national food system safety nets existed, the public relied on each other and the media to report on food adulteration concerns. You might even recognize some of these late 19th and early 20th century illustrations that warned consumers about common additives or aimed to convince a reader to join the Pure Food movement.

In light of the current FDA communications embargo, the public has taken to social media to share the latest recalls and provide general advise on how to navigate common food safety concerns without the federal administration’s support. The FDA is still posting recall alerts on their website (albeit several clicks in), but they aren’t able to effectively communicate with the public through email or via news outlets which help call consumers to action.

Allergist and clinical immunologist, Dr. Zachary Rubin, known as @rubin_allergy on social media has been posting daily updates with the various recalls and explaining their magnitude since January 25. We’re still in the early days of this administration, and while this situation is serious, consumer responses have been orderly. But if you start seeing AI art of trad-skeletons serving raw milk out of the back of a SUV, do know that we’re in trouble.

RFK Jr. might be confirmed in the coming days. The public communications embargo on federal health agencies might be lifted soon, but only time will tell what internal chaos is being brewed during their forced silence. Their federally mandated mission to protect the consumer public might change and there might be more communication embargos in the future.

An unregulated US food system is part of our shared and readily available history (these aren’t secrets and we only touched the tip of the pure food movement iceberg here). A very easy way to take political action right now is to arm yourself with this food history and the important progress of food regulation and share it with others. Oh and also don’t drink raw milk.

Pairs well with:

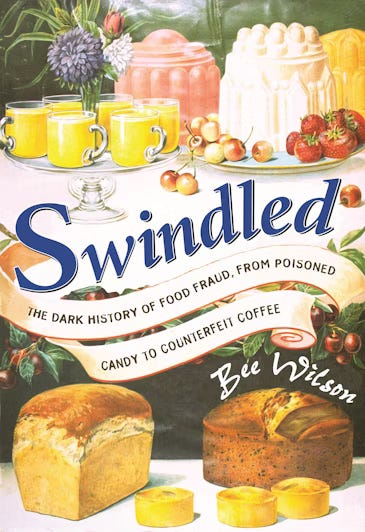

I love anything by Bee Wilson, but Swindled feels especially timely at the moment. Read it and pass it on!

Obsessed with Bee Wilson, great rec. And fantastic piece, thank you for writing this!