For many in my age range (I’m smack dab in the middle of the millennial demographic), the act of “adding guac” to a burrito order is the ultimate demonstration of wealth (for whatever reason our generational financial acumen is measured in avocados). During our lifetime, adding guac became the meme-ified symbol of the haves as opposed to the guac-less havenots. (This avocado-centric reference is related to the larger theme of millennial money habits impacted unduly by our insatiable hunger for avocado toast.) Growing up in Texas, where guac and avocados were relatively affordable if not quotidian, a different food took up the mantel of being the edible status symbol: real maple syrup.

Despite my slightly-crunchier parents’ efforts to eschew processed foods, I honestly can’t remember ever having real maple syrup growing up at home (it’s all my dad uses now though, gah). We were a pancake syrup household. On special occasions at restaurants, I remember the distinctly luxurious feeling of saying “why not?” to the real maple syrup upcharge. And when I went away to college in Austin, where crunchy norms and access to organic/whole/natural foods far exceeded the options of my small hometown, the go-to pancake place—long known as the hippie dippie diner—still charged extra for a small metal ramekin of the good stuff. For younger me, real maple syrup denoted all the same things that guac means for modern-day millennials, but it also carried implications about class and worldliness; after all, maple syrup came from very different trees many miles away from Texas. Despite the distance, our Texas pancakes still needed to be as close to American pancake-ness as possible. And as they say, the closer to maple syrup, the closer to God. (I’m sure someone says that.)

Last week, Food52 posted a video about the impending trade tariffs imposed by the Trump Administration that will inevitably impact our access to Canadian-produced maple syrup (in addition to other imported foodstuffs). While some regions in the United States can produce maple syrup, it isn’t enough to meet demand. According to Agri-Food Canada (similar to the USDA), behind Canada, the “United States was the second-largest producer, accounting for approximately 29% of global production” in 2023. Despite that ranking, a whopping 62.1% of Canadian maple syrup exports went to the United States. And even with our own locally produced product, United States-made maple syrup can still costs an average of $55 per gallon (or about $13-17 for one of those 32 oz small-handled jugs, depending upon where you shop for groceries). Nevertheless, we must have the maple syrup for our pancakes.

In the video, food creator Justin Sullivan shares three pancake topping alternatives while talking about the impact of the looming tariffs: a sausage gravy, pomegranate molasses and tahini, and a honey-miso butter. All great options (especially that gravy), but they aren’t really substitutes, especially when you’re trying to capture that iconic pancake-and-syrup combo. These alternatives are truly subpar when you think about all the socioeconomic feelings tied up with the classic plate of pancakes. Nowadays, an arguably trendy honey-miso butter pancake plate might be exactly what sells like, well, hot cakes. Past me would absolutely not have equated honey-miso butter with wealth or worldly thinking, and I argue that many other consumers would have felt similarly. We don’t have anything against miso, and honey is a fine sweetener, of course, but to a kid raised on pancake syrup (or other imitation stand-ins), real maple syrup dripped with status.

As a modern nation, we’re increasingly open to new foods and new food combinations, but when we expect something to taste a certain way, like a plate of pancakes, by god it better taste exactly like we know it should. There’s a lot you can tell about American eaters, their sociocultureconomic status, their age and major events they lived through (like wars, rations, agricultural events), and even how they were raised based on what they put on their pancakes. There’s the oddballs, of course, like my mother who preferred peanut butter and brown sugar on her pancakes, but mostly folks fall into just a few syrup categories.

There’s the real deal maple-syrup eaters. If they live in the North East, they likely get it locally or, if they’re extra lucky, they have their own trees to tap. If they live elsewhere, they likely bought the imported stuff. There are, of course, a few other pockets of maple producing regions across the nation (Texas even has sugar maples, but the weather doesn’t promote good sap production), but these barely make a dent on national consumer habits.

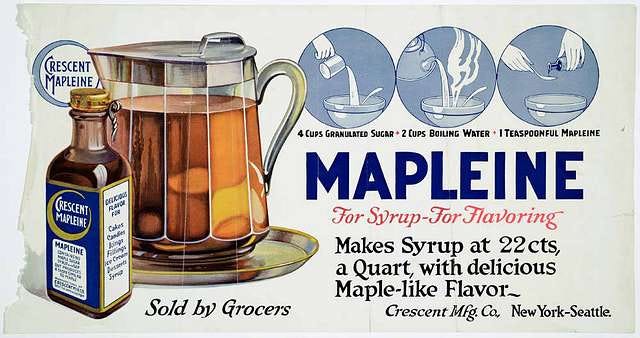

Then there’s the pancake syrup, sometimes known as “table syrup,” households, consumers of a far more affordable option so called because the syrup really just goes on pancakes (well, also waffles and French toast, though they aren’t the same kind of all-American foodstuffs now are they). This kind of syrup is often made up of high-fructose corn syrup and only contains imitation maple flavor. In the late 19th century, consumer demand for maple syrup resulted in the development of a variety of table syrups. These other syrups could be made with all manner of ingredients and attempts to emulate that tell-tale maple flavor created a fair amount of concern. These “deceptive imitations” were one of the first foods that led to the development of the FDA and the passing of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Due to tariff quotas related to cane sugar in the 1960s, the United States expanded the use of domestically produced corn syrup, specifically the use of cheaper high fructose corn syrup.

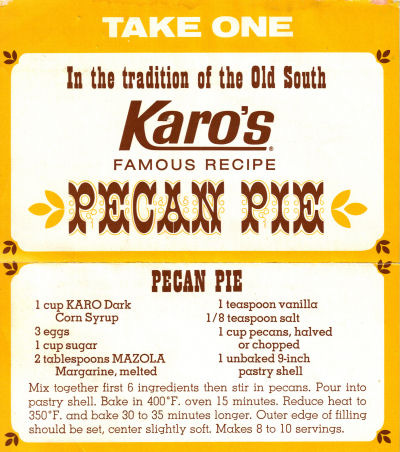

My grandparents, now in their 80s, always served Karo Syrup (a popular brand of corn syrup) with pancakes. If we were lucky, they had the Dark Karo Syrup in the pantry that had a little molasses in it for coloring; otherwise, we had to eat the traditional clear syrup that was thicker than honey and slowly oozed across the plate leaving a thick crystal clear varnish in its wake. Founded in 1902, Karo (pronounced Kay-roh in the south) was advertised as “The Great Spread for Daily Bread” and was considered a “table syrup.” Karo launched one of the largest targeted marketing campaigns of its time, specifically aimed at Mrs. Consumer through full-page ads in women’s magazines and free cookbooks centered on the syrups. Another common use for Karo, especially in the south, was as a sweetener in pecan pie. Many southerners’ pecan pie recipes come from the original Karo instructions (did I mention Karo started in New York and Chicago?). In the 1930s, the brand rolled out a new Waffle Syrup that fell somewhere between the light and dark offerings (this product is now called Karo Pancake Syrup and uses artificial maple flavoring much like other pancake syrups). I never knew this variety of Karo existed until writing this post.

Many folks in North Carolina, where I live now, have told me about pouring brown, sorghum syrup on pancakes and biscuits. The grassy stalks of the sorghum plant have a high sugar content which are pressed and the resulting juice is boiled to produce a thick and not-too-sweet syrup. Much like other boiled and reduced liquids (like pomegranate molasses), this syrup is often called sorghum molasses. This nomenclature frequently confuses folks, even other southerners, who are unfamiliar with sorghum, but know well the mineral-rich and often times bitter taste of actual molasses, the sweet syrupy byproduct of sugarcane or sugar beet sugar extraction.

All of these syrups share a complicated food history. For many decades, one popular brand of pancake syrup, formally known as Aunt Jemima, featured a racist caricature of a Black woman (the brand remade itself as the Pearl Milling Company in 2021). During the Civil War, amidst tariffs on can sugar and supply embargos, the American South relied heavily on sorghum syrup as a sugar substitute. Sorghum, however, was not native to the American South, but was an ancient grain from Africa and was likely brought to the United States, as food writer Ronni Lundy explains, to “serve as a cheap, familiar food for enslaved Africans, and to be used as animal feed.” Once the war was over, the panic was gone, and the far cheaper sugar beet became a better route to the mass production of sweetness, sorghum lost its shine. Until recently, and still in many ways, that national sugar craving was fueled by incredibly cheap high-fructose corn syrup laced with maple flavoring, just enough for proper American pancake verisimilitude.

Nutritional outcomes aside, these are all perfectly fine pancake garnishes; there is no right or wrong way to eat a pancake (I’m partial to sorghum with a sprinkle of brown sugar on top). Except, there is, of course, because pancakes are emphatically American and we’ve attached lots of feelings and morals to them and expect them to look, smell, and taste a specific way. We feel so strongly about the rightness of pancakes and syrup that we had to invent a maple syrup stand-in. And when others who couldn’t access or afford that imitation attempted to use other ingredients that had on hand, we looked down our noses at those less-American attempts. We passed on the practical and logical possibility of a national sorghum sugar crop. We chose alternative sweeteners and blessed them with enough maple-ness. But we also offered, alongside — for a small fee, of course — a taste of the real deal, a monetary option to demonstrate one’s dedication to the American dream.

Thankfully, we as a society tend to be more polite about our dietary differences these days and are far more open to variations on a theme like those syrup alts dreamt up by Food52 because we are open to trying more foods and new-to-us food combinations. That said, these tariffs aren’t coming out of thin air or from a civil discourse between two countries.

This looming maple syrup shortage is a byproduct of hate and stubborn (and increasingly dangerous) nationalism.

This particular potential shortage obviously isn’t a dire situation, but many of us have already experienced the subtle Othering that accompanies what one puts on top of pancakes. It’s not even the kind of thing that results in public mocking (unlike other foods that Americans have historically made fun of). It nonetheless feels odd to grow up and learn that your syrup wasn’t quite right or to be keenly aware of your financial situation even as a young child all because of a luxury tree sap that we, at some point in history, deemed the only thing appropriate to pour over flat cakes one eats at breakfast.

We will be forced to reckon with the maple syrup we do have within our borders and that wont last long and it will likely be too expensive for many American families to buy regularly, if at all (syrup isn’t a necessity *she said mostly to remind herself*). And now that Trump has pissed off Maine, the third largest maple producing state, there might be an even smaller national maple syrup stock than we originally calculated.

I can’t imagine we’ll stop making pancakes (because they’re an awesome food and such an easy vehicle for hidden vegetables, fruits, and even the odd protein), but we’ll inevitably and increasingly need to turn to syrup alternatives. Some eaters will go quirky, like my mother, and find solace in other sweet toppings, but many folks will miss the peculiarly special flavor and texture that only maple syrup provides. Table syrups will be our breakfast saviors, but the maple syrup upcharge will reign.

I grew up in Canada and we always had pancake syrup or corn syrup on the table. The real deal blew my mind in my young adulthood, and I can never go back. Thank goodness I live in Canada! I hadn’t given any thought to how the tariffs would impact our maple syrup export to the U.S.

Despite living in the Northeast, back in the 1960s modern housewives embraced the notion of artificially flavored maple syrup as being progressive - just like using canned veggies, TV dinners, and baby formula made of Karo syrup 😮 Dutch strop is a yummy alternative - traditionally made of beetroot😀